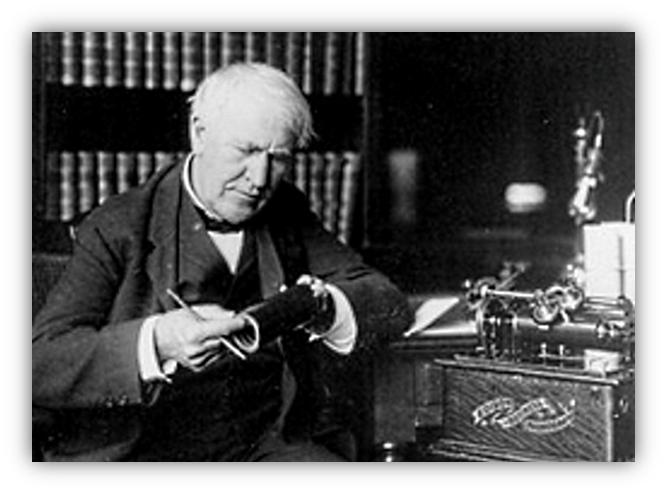

You all know Thomas Edison, so I won’t go into his entire biography.

But indulge me in this story of visiting his winter home in Fort Myers, Florida,

I went with my wife and her parents. My father-in-law was on crutches at the time but he got around pretty well. He also had a new camcorder and recorded a lot of our visit. At least, he thought he did.

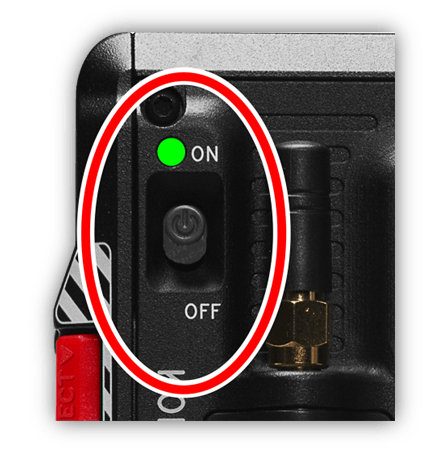

With the camcorder hanging around his neck, we’d go to a display and he’d prop himself on his crutches, film whatever we were looking at, then turn the camera off and let it dangle around his neck as we moved on to the next site.

At an early stop, however, he thought he turned it off but somehow didn’t. From that point on, he was turning it off when he thought he was turning it on and vice versa.

We now have a 45 minute long video of the ground, his feet, and his crutches.

While Edison was a big part of inventing and improving motion pictures, which led to my father-in-law’s camcorder, let’s dig into his invention of the phonograph.

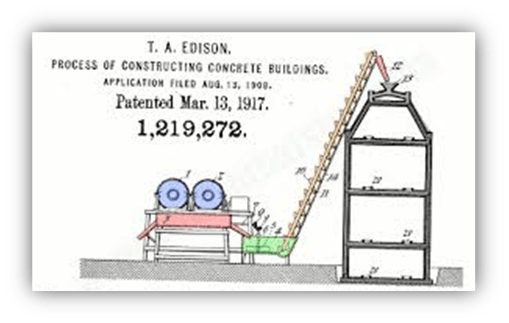

Over the course of his life, Edison was granted 1,093 patents:

For inventions like: the light bulb, the magnetic iron ore separator, and the electrographic vote recorder. As well as for improvements to existing technologies, like:

The cement mixer,

The telegraph,

The typewriter, and many, many, more.

By the late 19th century, he was a well-established and famous inventor. He could have rested on his laurels — and the income they earned him — but his relentless curiosity and desire to innovate led him to experiment with sound recording and reproduction.

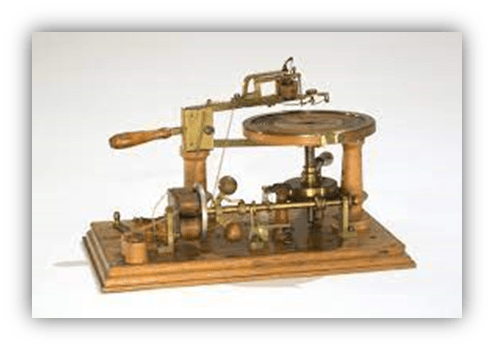

Edison’s idea for the phonograph came, in part, from his work on improving the telegraph and telephone. He was also familiar with the phonautograph, an earlier sound recording device invented by Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville in 1857, and he theorized that if sound vibrations could be recorded, they could be played back.

Scott’s phonautograph was the first device capable of recording sound waves, though they could only be seen, not heard.

Still, it demonstrated that sound could be transformed into a physical medium, and Edison built upon that. He thought that if he could record telephone messages, they could be replayed at a later time. This idea led him to experiment with a method for capturing sound waves and converting them into something physical.

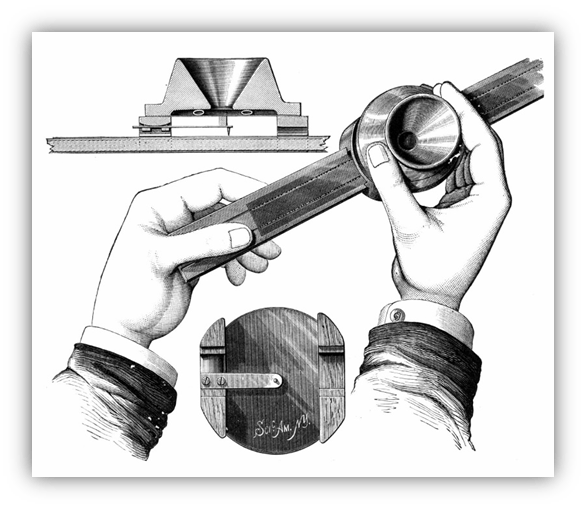

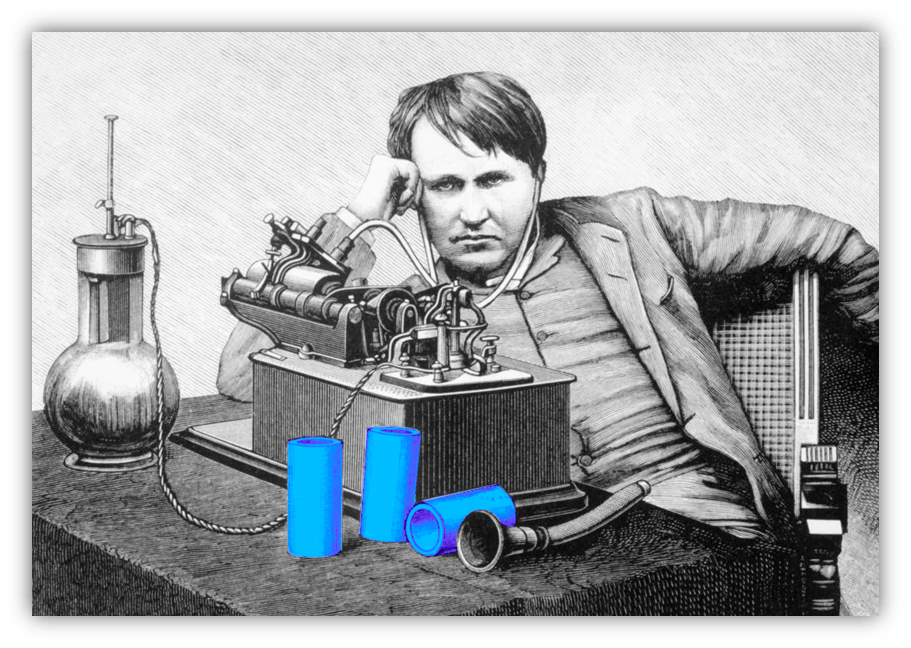

In July 1877, Edison began with a device similar to Scott’s phonautograph, but used a strip of paper coated with wax rather than lampblack.

He used a stylus connected to a diaphragm, which vibrated in response to sound waves. These vibrations were then transferred to the stylus, which inscribed the patterns onto the waxed paper.

Edison switched to a cylinder, as Scott had done, and replaced the waxed paper with tin foil. Sound waves would cause the diaphragm to vibrate, which in turn moved the stylus which etched a groove into the tin foil.

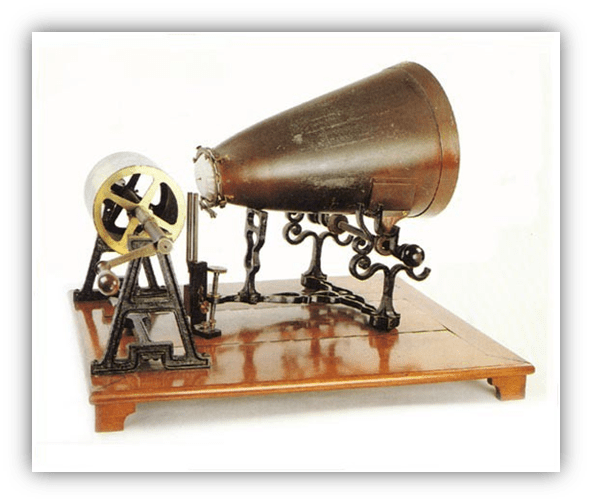

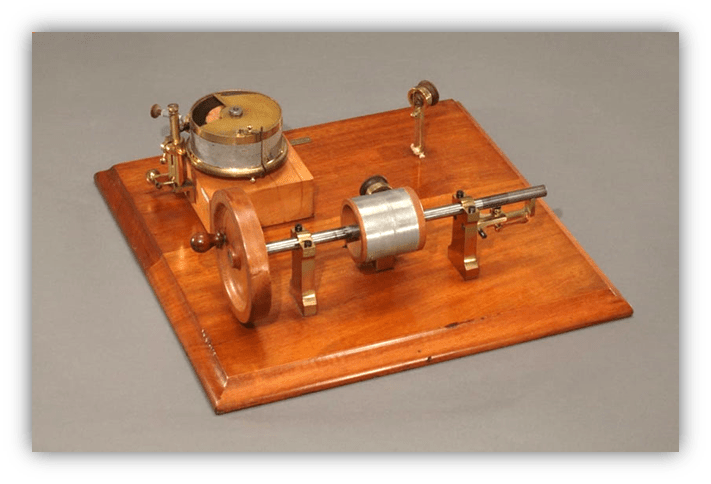

The key components of the phonograph were a hand-cranked cylinder, a stylus, and a diaphragm.

The user operated it by turning the crank and speaking into a mouthpiece, causing the diaphragm to vibrate. These vibrations wiggled the stylus, which etched a ragged groove into the tin foil wrapped around the spinning cylinder.

When the process was reversed, and the stylus traced the previously etched groove, the vibrations were recreated and amplified by the diaphragm, which reproduced the original sound. The diaphragm was the microphone when recording, and the speaker when listening.

On December 6, 1877, Edison conducted a successful demonstration of his tin foil phonograph. The first recorded and played back message was Edison reciting the nursery rhyme “Mary Had a Little Lamb.”

The recording was crude but the playback was recognizable, marking the first time in history that sound had been both captured and reproduced. Later, he said, “I was always afraid of things that worked the first time. Long experience proved that there were great drawbacks found generally before they could be got commercial; but here was something there was no doubt of.”

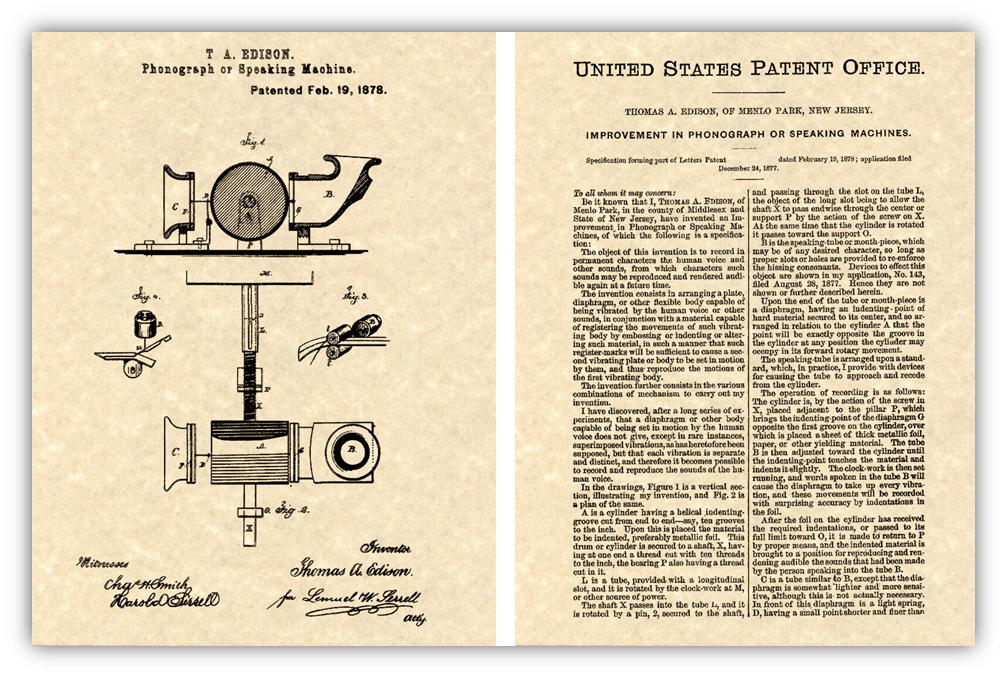

His recognition of the phonograph’s profit-making potential led him to quickly file for a patent, on December 24, 1877.

Granted on February 19, 1878, the patent described the phonograph as a device for recording and reproducing sound.

He thought the phonograph would be used for dictation, letter writing, and educational purposes. However, geniuses get bored easily and Edison moved on to other projects.

That left the phonograph with a few flaws. This allowed competitors, like Alexander Graham Bell’s Volta Laboratory, to make some advancements, contributing to the overall development of sound recording technology. Bell developed a floating needle that didn’t erode the grooves as quickly.

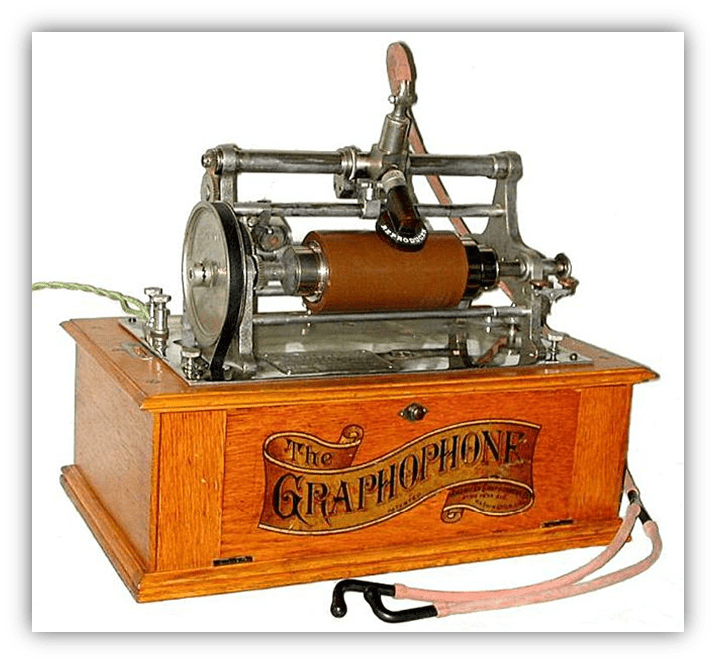

Chichester Bell and Charles Sumner Tainter developed the graphophone, which used wax cylinders and floating needles.

In 1887, they approached Edison about collaborating on its development but Edison thought he was the phonograph’s one and only inventor. He refused to partner with them, but that outside interest spurred Edison to revisit the phonograph.

After all, he loved the phonograph like one of his children. He said, “…I’ve made some machines; but this is my baby, and I expect it to grow up to be a big feller and support me in my old age.”

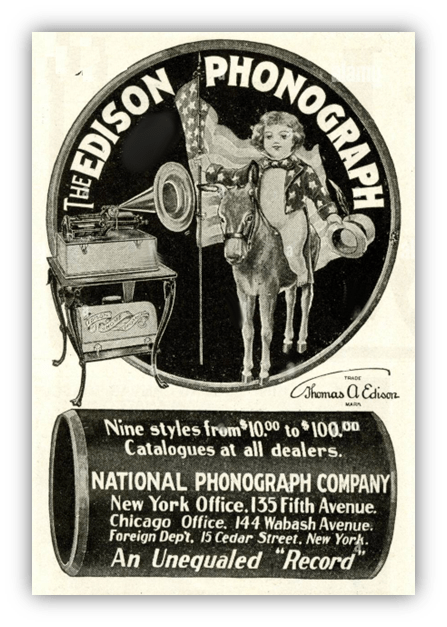

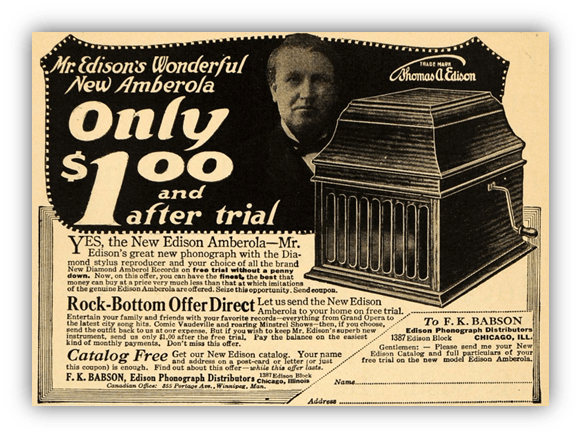

He started the Edison Speaking Phonograph Company to develop and market his invention.

However, the limitations of the tin foil cylinder, including its fragility and poor sound quality, made it hard to market. He used Bell and Tainter’s idea of replacing the tin foil cylinders with wax ones, which offered better durability and sound quality.

It didn’t take long for the public to start using the phonograph for listening to music. Edison — and Scott before him — had thought recording sound would mainly be used for dictation in the business world. Edison recognized that music was another possible use and came up with some new ones: elocution lessons, audiobooks for the blind, recording telephone calls and the final words of dying family members, clocks that audibly tell you it’s bedtime, preserving languages threatened with extinction, and more.

These are all visionary ideas, but music became the nearly exclusive use for sound recording.

And that presented a problem. Recordings were a one-at-a-time medium. In order to sell multiple copies of a song, the musicians would have to perform the song over and over again, once for each copy sold. Every recording was therefore different, if only slightly, but it wasn’t good for the musicians.

Nor was it good for the consumers who got copies recorded when the band was tired and/or bored. Nor was the time-consuming and costly process good for the Edison Speaking Phonograph Company.

Eventually, someone got the idea to record ten copies at the same time by using ten phonographs. That got ten times as many recordings made, but it still wasn’t optimal.

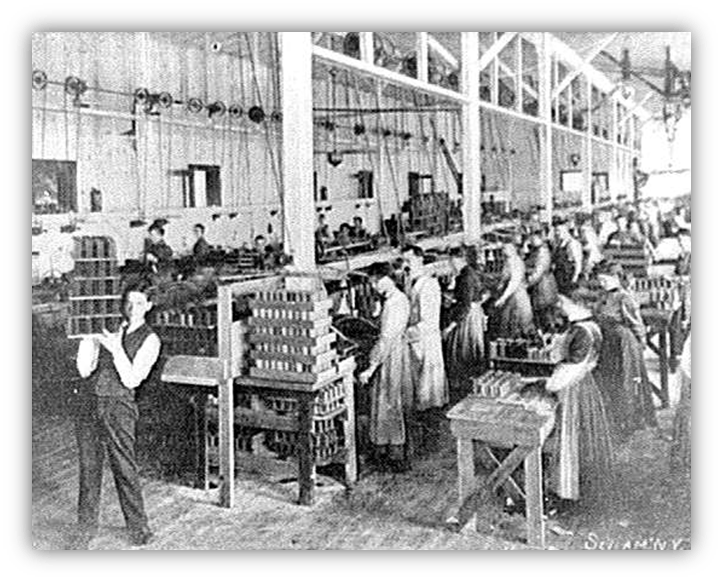

Edison started mass-producing duplicate wax cylinders in 1901.

The cylinders were molded, rather than engraved, and a harder wax was used. The result was referred to as “Gold Moulded” because gold powder was used as a conductor and the process gave off a gold vapor. Plus, anything with “Gold” in its name sounds fancy.

Edison’s company could produce about 150 cylinders a day. However, the market preferred the flat disc record we know and love today. (More on that in an upcoming installment.) Edison’s cylinders went the way of the Model T, but he didn’t abandon his cylinder customers just yet.

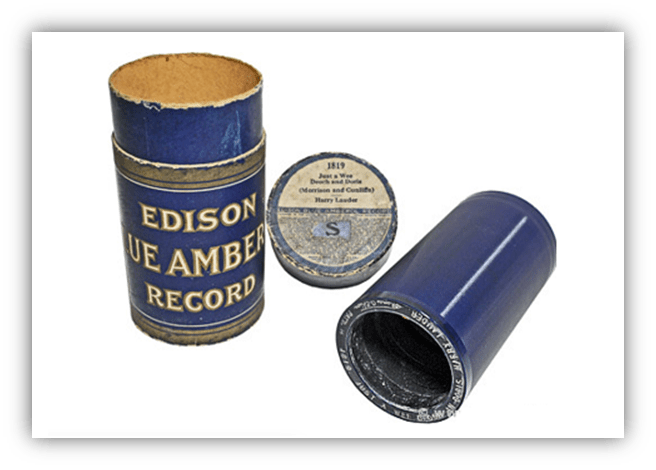

In 1912, he introduced the Blue Amberol Record, a cylinder with the best sound available at the time.

It was unbreakable, and he continued manufacturing them until 1929, but started selling the Edison Disc Phonograph in 1913. From 1915 on, most of the Blue Amberol cylinders were copies of the music recorded for his discs.

As brilliant as he was, Edison’s taste in music was a little outside the more popular choices of the day. That may be why he didn’t sell as many records as his competitors. Here’s his favorite song, “I’ll Take You Home Again, Kathleen,” as sung by Will Oakland and released on Blue Amberol in 1910.

The phonograph brought music performances from music halls to living rooms. It also preserved the voices and performances of historical figures, so we can now experience their ideas and music long after they’ve passed on to the great concert stage in the sky.

As production increased and prices dropped, the phonograph made music accessible to almost everyone.

It marked the switch from sheet music to recorded music, allowing people to hear music and the spoken word in previously unimaginable ways.

The downside is that fewer people played instruments for fun. They just listened to records and the radio instead. The upside of that downside is you can now buy old pianos cheap.

In a 1921 interview with The American Magazine, Edison said:

“Which do I consider my greatest invention? Well, my reply to that would be that I like the phonograph best.”

“Doubtless this is because I love music. And then it has brought so much joy into millions of homes all over this country, and, indeed, all over the world.”

“Music is so helpful to the human mind that it is naturally a source of satisfaction to me that I have helped in some way to make the very finest music available to millions who could not afford to pay the price and take the time necessary to hear the greatest artists sing and play.”

Let the author know that you liked their article with a “Green Thumb” Upvote!

Bring back Blue Amberol!

That recording sounds fantastic given its age. It’s almost eerie how it doesn’t sound eerie.

It’s interesting to think of a world where recorded performances couldn’t be duplicated.

On one hand, you’d have a bit more variety in the world. On the other, you’d have a lot of lukewarm takes of classic songs out there.

“She loves you. Yeah, yeah, yeah. Bully for you. We’re done. Next!”

Thanks for the history lesson, Bill!

I think I was prescribed blue Amberol at one time. Fixed what was ailin’ me.

I didn’t get into this because the article was getting too long, but part of the reason Blue Amberol sounded so good is the needle was always perpendicular to the groove. On a flat disc, the needle is on a tone arm that swivels. When the needle gets to the inner grooves, it’s at an angle and can’t pick up all the vibrations.

If you’re playing a 78rpm record (or a 45 or 12″ single) the beginning of the song will sound better than then ending. That’s at least part of the reason Edison stuck with the cylinder for so long. Still, the disc became more popular for reasons we’ll get to in a future installment.

I’ve seen those cylinders for sale at antique shoppes, but I’ve never actually seen one played in person. That would be a fun thing to do.

I have a Will Oakland song in my iTunes Music library. “Mother Machree” from 1910. (A #1 song according to Joel Whitburn). My copy was digitized (by someone) from Edison Amberol Blue #583.

Let us not forget that he also invented the talking doll!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BTWaAM_FqlU

Favorite quote-

“They were received not very well. Children found them to be a little on the scary side”.

Chucky awaits.

Hey, now …

Sorry, Chuck.

Just yanking your chain. 🙂 I actually hate that nickname.

The eerie has landed.

Yeah, we don’t talk about that anymore.

I love this. We visited the Ford & Edison winter estates a few years back. It’s definitely a must-see for anyone in the area. I wish I could say I’ve never done what your father-in-law did. I will have an article coming up soon that will cover the phonograph from a different and more personal angle, so I doubly appreciated reading this today.

Looking forward to it!

That Will Oakland song puts me in mind of Spike Milligan and The Goons. An unexpected inspiration perhaps for Spike in coming up with his silly voices for their musical numbers.

Is Blue Amberol the betamax to the VHS of the shellac / vinyl disc? Better quality sound but not as convenient.

That’s a great comparison.

One of my most prized possessions. Here’s a little demo:

https://youtube.com/shorts/N4sdCs1GcwU

It’s a 10!

Ha! I love it! Was that song sung by Nikola Tesla?