We’ve all been told that Guglielmo Marconi invented radio – and he did.

In 1895, he sent the first radio signal over several miles.

That was the start of wireless communication. Only six years later, he transmitted the first transatlantic signal, from Newfoundland to England.

It was only Morse code for the letter “S”, but it showed the enormous potential of communicating long-distance via radio waves.

However, this column is about musical inventors… so we’re going to skip Marconi. His contributions to broadcasting are astounding, but all he ever transmitted was Morse code. He thought about broadcasting voice and music, but he didn’t actually do it.

So who did?

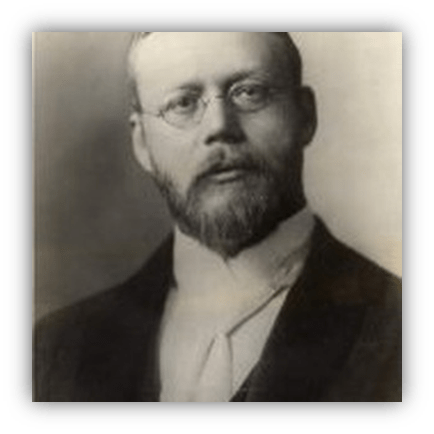

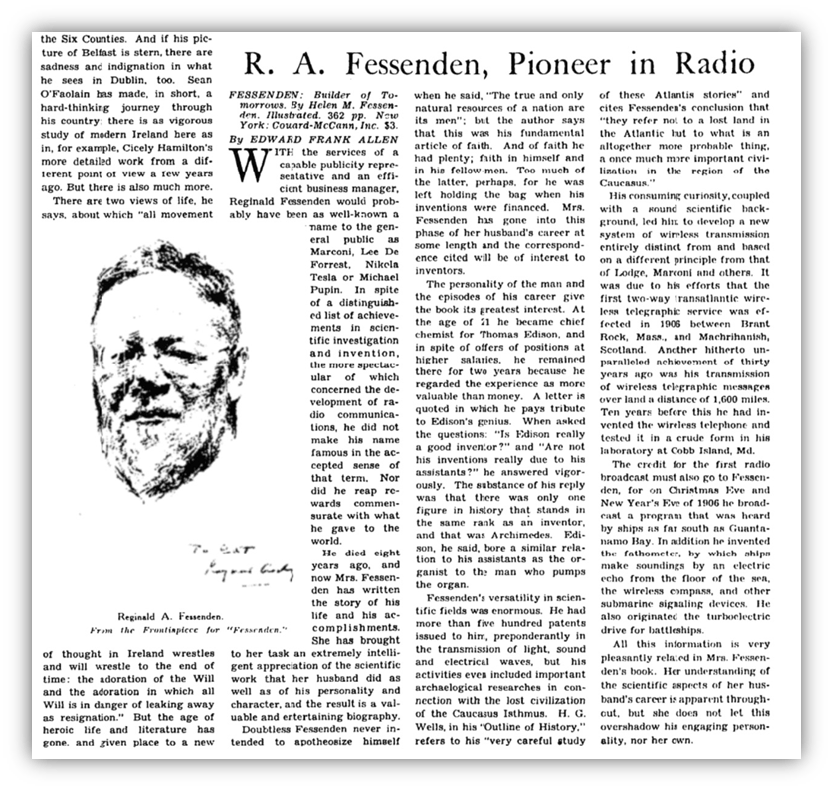

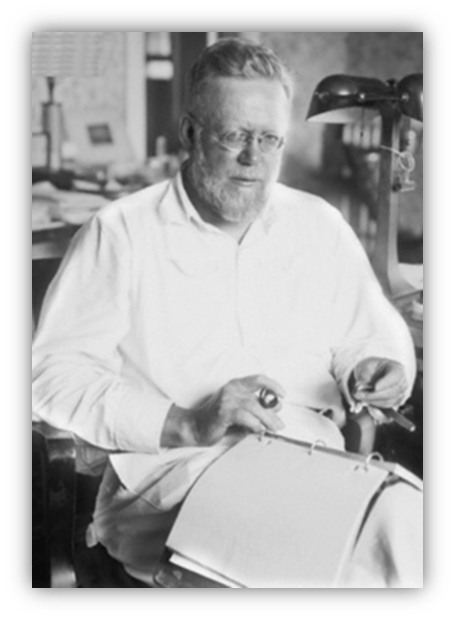

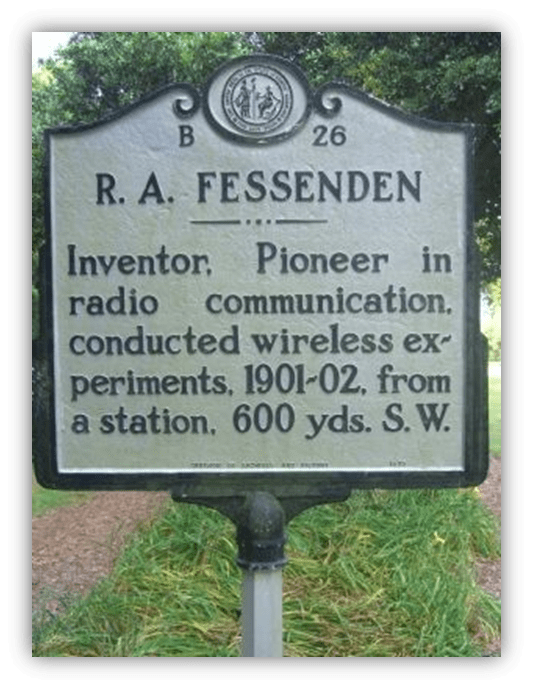

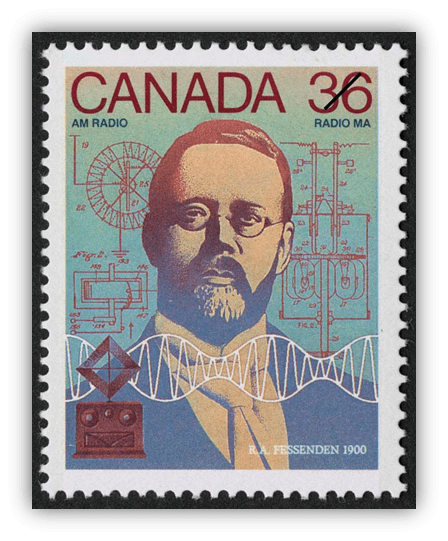

Meet Reginald Fessenden.

Reginald Aubrey Fessenden was born in East Bolton, Quebec, a dozen miles north of Vermont, in 1866.

His father was a pastor, so they moved often. His mother earned fame for founding both Empire Day and the Imperial Order, Daughters of the Empire.

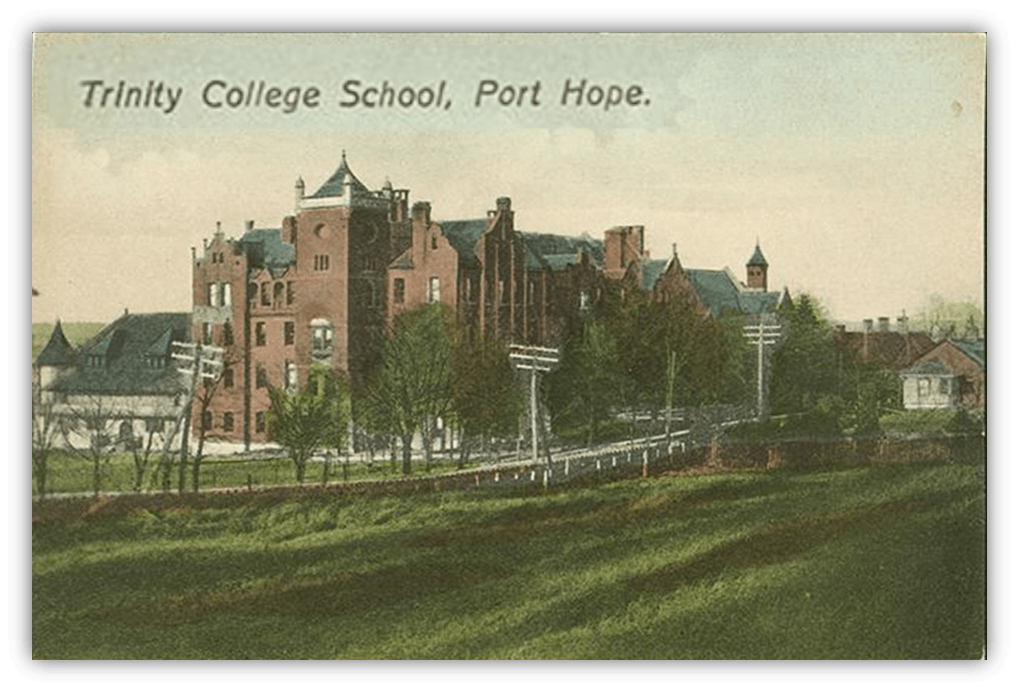

Fessenden studied at Trinity College School in Port Hope, Ontario. While there, he developed a keen interest in science.

It was said he would hide copies of Scientific American in his textbook so he could read it when he should have been studying Latin. He could be headstrong like that.

Fessenden also went to Bishop’s College in Sherbrooke, Quebec. He taught the younger students there French, Greek and Math as a part time job. With that teaching experience, he left before earning his degree to become headmaster of the Whitney Institute School in Bermuda.

The Institute was new, built after a hurricane with funding provided by the Whitney family.

There’s not much evidence of other staff so he may have been its only teacher. He spent his free time reading science books and thinking about wireless communication. He’d talk about science with anyone who would listen, and one of those people was Helen Trott, the daughter of one of the school’s board members.

While their courtship was serious, Helen’s father knew Fessenden’s salary, and that it couldn’t support a family. It didn’t help that Fessenden talked about sending voices across great distances through the air. Mr. Trott liked the young man, but such pie-in-the-sky daydreams were silly. When the two-year contract was up, the couple had to separate. Fessenden was 20.

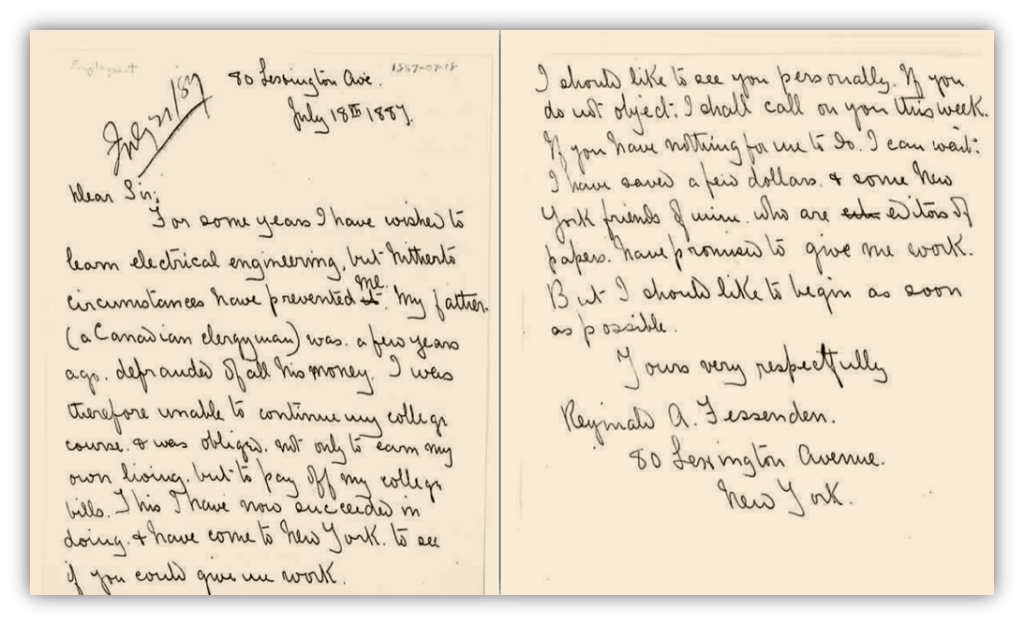

He moved to New York with the aim of working for Thomas Edison.

He approached Edison with a letter of introduction, to which Edison replied, “Am very busy. What do you know about electricity?”

Fessenden wrote back, “Do not know anything about electricity, but can learn pretty quick.”

Edison’s response was, “I have enough men now who do not know about electricity.”

Fessenden kept at it, hanging around Edison’s public projects. He became friends with a foreman at Edison Machine Works and was offered a position testing cables. His work showed promise and he quickly moved up the ladder to become Edison’s chief chemist. Edison took to calling him “Fessy.”

He traveled back to Bermuda in 1889 and brought with him his new prestige – meaning “money” – and one of Edison’s new phonographs.

A wax cylinder he brought was a message from Trott family members in New York. The cylinder wore out quickly, but some of the Trott family heard it and were impressed.

The following year, with her father’s blessing, Helen traveled to New York and married Fessenden.

Meanwhile, German physicist Heinrich Hertz was making headway in wireless transmission, and Fessenden talked with Edison about researching it, too.

Edison said they’d start as soon as he got back from the 1889 Exposition Universelle de Paris. By that time, however, the depression of the 1890s had the company in bad financial shape. The lab shut down. All the employees were laid off.

Fessenden went to work for Edison’s competitor, George Westinghouse, who had invented air brakes for trains.

Even so, Westinghouse’s business, like Edison’s, was hurt by the depression, and Fessenden was out of work again.

Purdue University hired him as a professor in their new Electrical Engineering department. In 1893, he helped Westinghouse install the demonstration lights at the World’s Fair in Chicago, and Westinghouse recommended him as the chair of the Electrical Engineering department at the newly formed Western University of Pennsylvania in 1893.

The chair position meant more pay and he was able to afford a bigger house, but he still had more research files than he had room for. He began photographing all his files. You might think that photos take the same space as the files themselves.

That’s why Fessenden invented and received a patent for what he called “micro-photography.” We now call it microfilm.

Until this time, it was thought that radio waves “whiplashed” like a thrown rope.

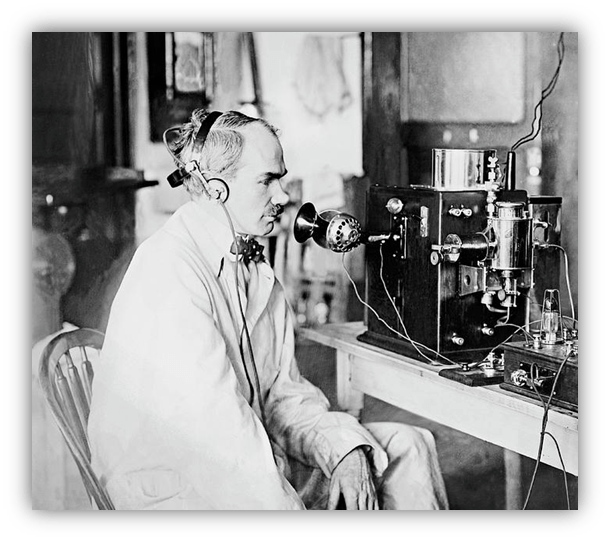

But Hertz proved the existence of electromagnetic waves and measured their wavelength, frequency, and speed. With this new understanding, Fessenden imagined that sound waves, as shown visually by Scott and Edison, could modulate radio waves at their own frequency. If so, the receiver, which currently picked up only the dots and dashes of Morse code, could easily transform them to sound again.

In their obituary for Fessenden, years later, the New York Times said, “The whiplash theory faded gradually out of men’s minds and was replaced by the continuous wave one with all too little credit to the man who had been right….”

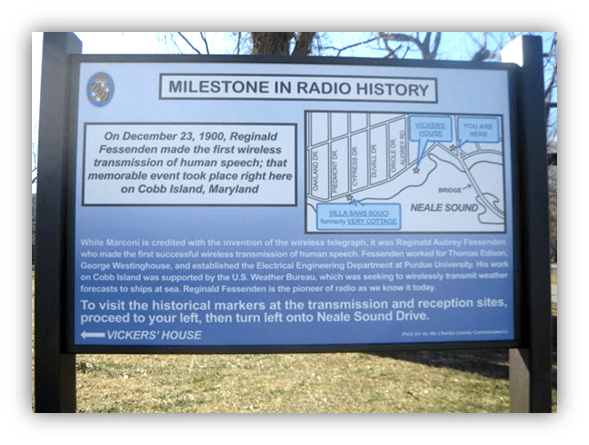

At the turn of the century, Fessenden left the university to work on radio transmissions for the U.S. Weather Bureau.

The agency wanted to be able to send weather alerts quickly over long distances. They were thinking about Morse code — and Fessenden did succeed in transmitting signals over 60 miles — but he pursued transmitting voice over radio.

Accounts vary about what the first words spoken and received by radio were, but most say it was, “One, two, three, four. Is it snowing where you are, Mr. Thiessen? If it is, telegraph back and let me know.”

His assistant was only a mile away so Fessenden knew whether it was snowing or not, but this was the first time human speech had been transmitted and received over radio waves. The words didn’t have to be great. The quality of the received sound didn’t have to be great. The main point is that it worked.

Few people noticed. Marconi sending a single letter “S” across the Atlantic was more interesting because of the distance. It’s an impressive feat, but it’s just controlling electrical spasms, which isn’t nearly as difficult as sending and receiving sound through thin air.

In 1902, Fessenden came up with a new way to convert high-frequency radio signals to lower frequencies, which made them easier to control and amplify. He called it a heterodyne, combining two Greek words: hetero, meaning different, and dyne, meaning force.

A decade later, Edwin Howard Armstrong improved Fessenden’s work and developed the super heterodyne, which is the guts of tuners in radios and TVs even now.

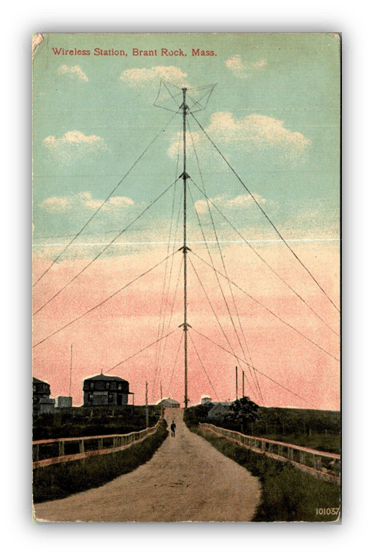

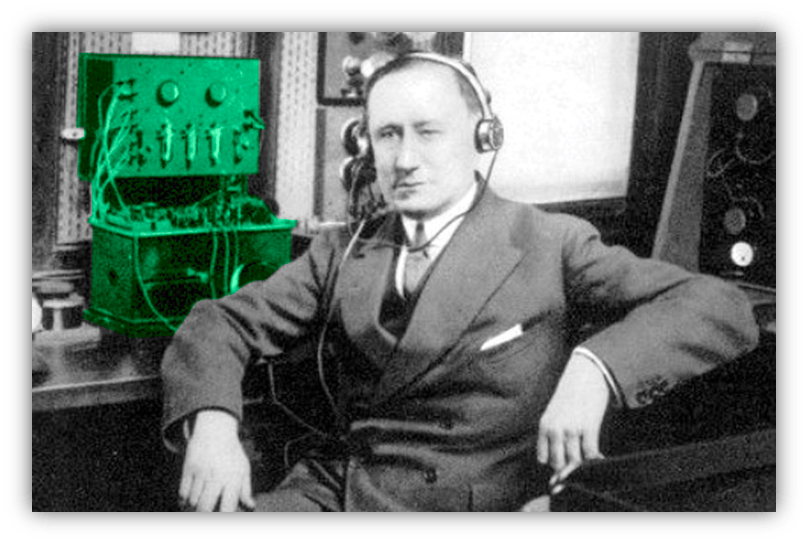

Fessenden left the Weather service to start the National Electric Signalling Company (NESCO) with investors Thomas H. Given and Hay Walker.

He set up antennas in Brant Rock, Massachusetts and Machrihanish, Scotland, about 3,000 miles apart, and transmitted and received Morse code in both directions. NESCO began selling this service, however, a storm destroyed the Machrihanish station less than a year later, and NESCO didn’t replace it.

During that year, Fessenden began experimenting with voice transmissions to fishing vessels. He would broadcast the current market prices for fish so they would know what to expect when they got back to port. The crews on these ships would be the first audience for music on the radio.

On Christmas Eve, 1906, and again on New Year’s Eve, Fessenden messaged to be ready for a special broadcast. He played a phonograph of Handel’s “Largo,” performed “O Holy Night” on the violin, sang Gounod’s “Adore and be Still,” and read from the Gospel according to Luke. It includes the bit that goes, “Glory to God in the highest and on earth peace to men of good will.”

It’s worth noting that Lee De Forest claimed to be the first to transmit music over the airwaves. In an unpublicized test in 1907, he played Eugenia Farrar’s “I Love You Truly.”

This is, of course, after Fessenden’s broadcasts, and De Forest had a history of false claims and altercations, so we can’t give him much credence here anyway. It’s likely, however, that a 1909 broadcast by his mother-in-law, Harriot Stanton Blatch, supporting women’s suffrage may have been the first speech on radio.

While Fessenden’s holiday broadcasts fascinated the fishermen at sea, the general public didn’t pay much attention. NESCO’s investors lost faith in him and his temper didn’t help matters. One of his employees, Roy Weagant, said, “He could be very nice at times, but only at times.” There was another incident when Fessenden told an assistant, “Don’t try to think, you haven’t got the brains for it.”

NESCO schemed to get rid of him, sent him to a conference, and raided his house while he, Helen, and their two children were gone, taking his papers and prototypes.

He was so bitter that he never worked on radio again.

Unemployed, Fessenden invented various items. Including a way to amplify sound by sending it through a violin’s body — but none brought much income. He and Helen began selling their belongings to make ends meet.

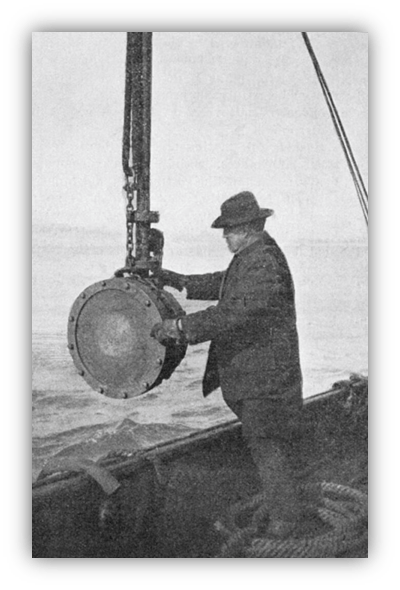

In 1912, he found employment with the Submarine Signal Company and worked on communications between subs. He invented an oscillator that created sound waves. These waves travel through the water, bounce off objects, and echo back.

By timing how long it takes to hear the echo, distances between the sub and other objects — another sub, an undersea mountain, or the sea floor — can be calculated. With the same device, Fessenden had invented both sonar and the depth finder.

That same year, the Titanic struck an iceberg. Sonar became essential on any ocean going vessel after that.

When WWI broke out, the Fessendens moved to London to help with the war effort. He developed hydrophones, which could be used to listen for the propellers on enemy ships. He also proposed an airplane engine capable of carrying troops to the battlefield, but it was too early in the field of aviation for that to be practical.

Rewarded handsomely for his contributions, particularly for the depth-finder, he returned to the U.S. and hired lawyers to get what he felt he was due for his earlier inventions.

In 1928, they reached a settlement. He and Helen maintained their house in Boston and bought another in Bermuda where he used the tides in and out of Harrington Sound to generate electricity.

Their life together was a series of ups and downs like a radio wave, with periods of success and wealth followed by periods of failure and near-destitution.

His scientific genius and generally gentile disposition was offset by his ornery tendencies and grudge-holding. Maybe it was those negative characteristics that kept his name from being as well-known as his inventions.

Helen wrote his epitaph when he died in 1932.

His tombstone in Bermuda is in both English and Egyptian hieroglyphs which say, “I am yesterday and I know tomorrow.”

Let the author know that you liked their article with a “Green Thumb” Upvote!

An Edison and Westinghouse-adjacent inventor with significant Canadian, US, and Bermudan connections. That alone is pretty interesting.

Was the “S” that Marconi first sent out via Morse Code? Because if not, then it would be impressive for more than just distance. “Was that an S…or an F??”

Really enjoying the series so far. No oscillations in that respect…except for in my brain.

Yes, just an “S” in Morse code. I have no idea why he didn’t go for more. It’s sort of surprising.

And thanks!

You can’t keep a good man down. Or an ornery one.

Maybe the rejections spurred him on to prove people wrong.

Never heard of Fessenden so great to shine a light on him. Whereas Marconi….everyone knows he plays the mamba.

Fascinating as ever.

That was a great look into someone I’d never heard of, who certainly earned moments in the spotlight. And that tale of his house being raided by his employer was heinously chilling. Great job, Bill.

WOT? The sound broadcast pioneer of radio also was associated with Purdue AND the National Weather Bureau???? I love it! Sounds like a fascinating guy. And I like the happy ending.