Music Theory For Non-Musicians

…if there was ever an art where breaking the rules is one of the rules, it’s music.

redditor u/COMPRIMENS

This occasional series is about how music is made, and it’s for people who don’t already make music. It’s part music appreciation and part music theory.

I hope to cover rhythm, melody, intervals, chords, inversions, and more. Maybe we’ll get into extended chords and modes. Let’s see!

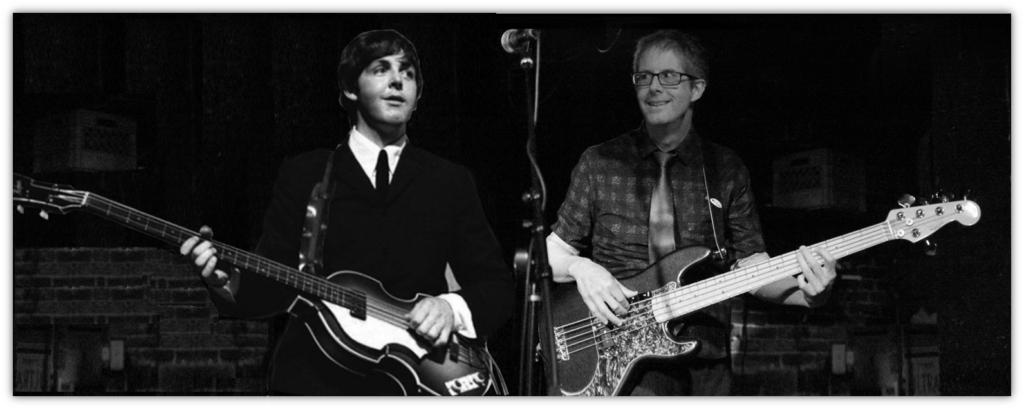

Paul McCartney and I have so many things in common:

• We’re both bass players:

• We both have gray hair:

• Neither of us can read sheet music, and…

… well, that’s pretty much it.

I suspect that, like me, he could pick out the notes on a musical staff one by one and eventually figure them out.

The mnemonic Every Good Boy Deserves Fudge comes in handy. Trained musicians, however, can play what’s on the printed page while reading it for the first time. That’s just mind boggling. I mean, look at this cello chart:

And that’s just the first four lines!

In a sixty piece orchestra, everyone must play their exact part, no more, no less. There’s no improvising. That’s why each player goes through years of lessons and schooling to learn what all these symbols mean.

I can see that it’s in the key of G major, indicated by the single # at the beginning, and that it’s in common time, which is what the C means. (Common time is also known as 4/4.) Since this is the cello part, there are a bunch of symbols for how to use the bow on particular notes. I really don’t understand those. And it changes from bass clef to, what is that, tenor clef?

Good grief. That’s another layer of difficulty.

Figuring out all the individual notes that would take me an hour. I haven’t internalized them so I’d have to count each line on the staff to get it. Especially those extra lines above the staff.

Next time you go to the symphony, keep in mind that they’ll be unfamiliar with some of the pieces they’ll play. Sure, they’ll all know Beethoven’s Fifth, but they’ll often play more obscure pieces, including world premieres. Some members may have seen the sheet music for the first time during that afternoon’s rehearsal. That’s why they study for years, so they can look at all that gobbledygook on the page and turn it into the music the composer imagined.

In the pop/rock world, session musicians face a similar challenge. They’re also asked to help the artist achieve the sound and feel of a song, without having heard it before. There might be a demo to listen to, and sometimes there will be traditional sheet music, but it’s often just the artist saying, “It goes like this.” A quick listen and verbal instructions, and that’s it. Sometimes the artist isn’t even sure what he wants.

Sometimes the session player creates something better than the artist imagined. Bassist Carol Kaye famously came up with her part for Sonny and Cher’s The Beat Goes On during the session. It totally defines the song.

In sessions like that, the artist will just play the song through and the musicians will take notes. Then they run through it a couple times and hit the Record button.

To make it sound like a song and not just a jam, session musicians have to be every bit as talented as classical players.

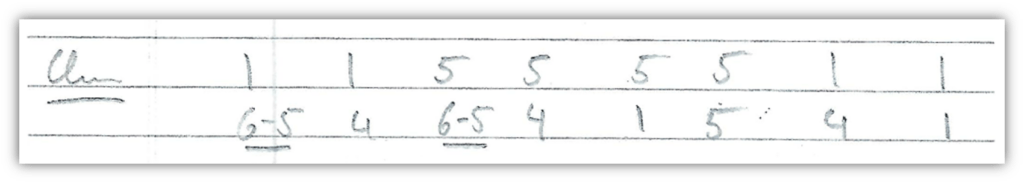

In the 1950s and 60s, session players in Nashville developed their own shorthand for writing charts. It’s still in use today. If I’m filling in with a Nashville artist I haven’t played with before, I might get a sheet of paper that looks like this.

This is a chart for a song called Careless by Laura McGhee. I found it by going through my charts looking for something to include in this article and it has many of the things you’ll typically find in a Nashville numbers chart.

Laura is a Scottish singer/songwriter, she plays guitar and violin, and she lived here in Nashville for a few years. The story of how I met her is almost worthy of an entire tnocs.com article, but that’s for another time. Anyway, I still have the chart, ten years later.

Always keep charts. You never know when you’ll need them again.

At the top of the chart, you’ll see the letter C in a circle. That means the song is in the key of C. However, the C has been crossed out and replaced with a D in my fairly sloppy handwriting. This is the absolute genius of the Nashville number system. If you decide to do a song in another key, you just replace the letter in the circle. You can’t do that with the sheet music for an entire orchestra.

Parenthetically, the number one reason for changing a song’s key is the singer may find it’s too low or high for their voice. If I remember correctly, that’s what happened here. Laura wrote the song in C but decided it was a little low and bumped it up to D. Rewriting the chart was just a matter of crossing out the C and writing in a D.

I won’t ask you to name the notes of the D major scale, I’ll just tell you. Starting on D and using that familiar major scale pattern – whole step, whole step, half step, whole step, whole step, whole step, half step – the D major scale is D, E, F#, G, A, B, C#, and D.

Down the left hand side of the page, you’ll see the verses and choruses labeled. Let’s skip the first verse for the moment and go to the easier chorus.

It starts with the number 1. That means to play the chord that uses the first note in the scale as its root. We’re in D, so the 1 represents D major.

Every time you see a number, it means to play that chord for one measure unless there are instructions otherwise. So we’ll play D major for a measure. How many beats in a measure? Well, it doesn’t say, so we can safely assume it’s in four. That’s how common common time is. It’s the default.

So the first 1 represents a D major played for a measure. That’s followed by another 1, which means to play D major for another measure. So that’s two measures of D major.

Then there comes a 5. In fact, there’s four of them in a row. The fifth note of the D major scale is A, so we’ll play A major for four measures. Then there are two 1’s, so it’s another two measures of the 1 chord, or D major.

Then comes a 6 with a dash and a 5, and both have a single line under them. The dash means to play a minor chord. The sixth note of the D major scale is B, so 6- means B minor. And we already know that the 5 is an A major. The line under them indicates that together they take up a single measure. Since there are no other markings, we assume that means two beats of B minor – 1, 2 – and two beats of A major – 3, 4.

That measure is followed by a 4. The fourth note of D major is G, so that means a measure of G major. Then that little “6-5 4” sequence repeats, so it’s two beats of B minor, two beats of A major, and a full measure of G major.

The chorus ends with a measure of 1 (D major), a measure of 5 (A major), a measure of 4 (G major), and a measure of 1 (D major).

Make sense? Each number tells you what note of the scale to use as the root of the chord. A dash tells you it’s a minor chord, no dash means it’s major. So far, so good.

Let’s go back to the top and talk about what’s happening in the first verse.

It starts with 6- (pronounced “six minor”), which we’ve already figured out is B minor, but there’s a diamond around it, and there’s a curved line linking it to another 6- in a diamond. Diamonds mean to hit the chord once and let it ring for a measure. In this case, there are two diamonds linked together so we’ll let that B minor ring for two measures. The same thing happens again, so we’ll hit another B minor and hold it for two measures.

That’s followed by two more linked diamonds but this time they have 3- (pronounced “three minor”) in them. The third note of the D major scale is F#, so we’ll hit an F# minor and let it ring for two measures. Then there’s two more measures of B minor, again in linked diamonds.

Then the diamonds go away and we have 6- four times. That means four measures of B minor, but no longer letting the notes ring, so we’ll play them in rhythm. What rhythm? Well, there’s nothing on the chart to indicate that, so we’ll have to rely on instructions from the artist, or go on pure gut instinct. Fortunately, I had copies of all the songs before I even met Laura.

There are two measures of 3- (F# minor) and then a measure of 5 (A major). Finally, there’s a 5 and then a ⅓. Both of these are underlined which, again, means they take up a measure together, two beats each. The ⅓ means that it’s a 1 chord (D major) but the bass plays a 3 (F#).

This measure also has four dots on an incline over it. That means to emphasize the four notes beats and get louder over the course of them.

The third line of the verse acts as a sort of pre-chorus. It’s one measure each of 4 (G major), 5 (A major), 6- (B minor), and 4 (G major). The last four measures are 1 (D major), 5 (A major), 4 (G major), and then 1 (D major) for half a measure and 5 (A major) for half a measure.

That’s all the symbols used on this particular chart but there are others commonly used in the Nashville number system. It was developed by people who understood music but either didn’t know standard notation or didn’t have time for it. Studio time is expensive, you know.

While some folks will pooh pooh “uneducated” country musicians, they sure came up with an ingenious way to tell each other how to play songs. It’s really hard to make things easy, and they did it. It’s music theory in miniature.

Try listening to “Care Less” and following along with the chart above. Laura’s video is here:

Let the author know that you liked their article with a “heart” upvote!

I clicked becaused the Nashville system confounded me when I first heard of it two months ago. But when you followed Sir Paul’s picture with sheet music, I thought, “If it were a G clef, that would be fun to try!”

Will read when I have more time to crack the Music City code.

Wow, this is amazing! I love this kind of thing, where you think there’s just one way of communicating something, or there really is an established standard, and it turns out that that’s not remotely true. It puts me in mind other systems, like shape-note singing or the hand signals of the Chicago Mercantile Exchange or the Deseret alphabet. So thank you for this insight into an alternate musical notation system. I have so many questions:

Do session musicians in other regions have their own systems? If not, how do they manage?

I assume it’s up to player discretion, or verbal instruction, about which minor chord to play?

What do percussionists and horn players do?

These are very good questions, mumchance, and I’m not sure I have answers. I’m not familiar with either the Chicago Mercantile Exchange or the Deseret alphabet, so I guess I have some research to do.

After reading this article, the lovely Ms. Virgindog asked pretty much the same question about regional systems, though she phrased it, “What did the musicians do up north?” Before moving to Nashville, all I ever got was charts with the chord names, if I got anything at all. It might be a different level of professionalism, because everyone I’ve played with here are pros. There are fewer musicians in New England and Florida, so I played with whoever I could regardless of status.

As for minor chords, it’s usually not up to the player’s discretion, especially in a band setting where you all have to play the same thing. Have a look at S1:E5 where I talk about why some chords are major and some are minor (and one is diminished) in any major scale. Basically, the notes of each chord have to be within the set of notes in the scale. The 1, 4, and 5 chord in any scale are major. The 2, 3, and 6 chords are minor. And the 7 chord is diminished. You can always assume that, though there will be exceptions.

Drummers have their own shorthand, though it’s pretty close to the standard notation for classical percussion. And horn players will read Nashville charts but they share their own slang. I was at a blues jam once where there was a sax and trumpet player on the stage at the same time. One said something to the other and they started playing parts in unison. I have not idea what she said but they sounded great.

Thanks for the detailed reply! Re-reading S1:E5 made me realize that I was confusing minor chords with minor scales, and I was imagining that there would be different chords depending on whether it was a harmonic or chromatic or whatever scale, which I see now is not the case.

How long did it take you to get used to reading the Nashville charts?

Not long, really. The only problem is everyone writes their charts in slightly different ways. Some people don’t put the dash after the 6 because they assume you should know that the 6 chord is always minor (except when it isn’t). But the system itself is so intuitive that I caught on pretty quickly.

But the system itself is so intuitive that I caught on pretty quickly.

Hence why you’re our teacher!

Was on vacation in Kiawah (among other places), so electronics took a backseat. Sorry for the delay, V-Dog, but I have questions (I was never the student in the front of the class, hand raised, so this is a whole new experience for me):

Oh, boy, each of these could be an article on their own. I’ll try to be brief, but keep them in mind for future editions.

Hope this makes sense, but I’m here all week!

This is totally going off the rails, but the thing about non-Nashville bands rehearsing the song in a single key reminds me of the scene at the end of “Singin’ in the Rain” where Kathy Seldon is going to sing the title song from behind the curtain while Lena Lamont lip syncs — the conductor of the pit orchestra asks what key, and Kathy, by way of Lena, calls for the title song in Ab, and the orchestra just ups and plays it. The fact that Comden and Green went so far as to add that whole exchange always made me think that this was at least a plausible scenario, but now I’m not sure — how good would that (fictional) orchestra have to be to be able to transpose on the fly like that? (Giving them the benefit of the doubt for even knowing it — practically everybody else on screen knows it too, so why not them?)

I remember the scene, but not clearly. If they were reading sheet music then it’s another of Hollywood’s mistakes, like a conversation in a car when the driver looks at the other person instead of the road. Twoset Violin make fun of Hollywood and Bollywood when they show actors pretending to play violin but making it obvious they never touched one before. Here’s the latest example:

While it’s likely that some players in the orchestra could transpose on the fly, the chances that all of them could is slim. Still, the scene reinforced that Kathy was the real talent, and that was important to the film.